Early-morning 11 August, 1784

Sorrentina docks

Lorsagne had no love of the sea, but the need to accomplish her business in both Paris and her home in the Haut-Medoc before returning to Sorrentina for her godchilds christening over-ruled her dislike of cramped, smelly cabins allotted to passengers whose money could buy speed of travel but precious little comfort.

Her belongings already stowed, she stretched herself out on the narrow cot in the tiny cabin and listened to the shouts and calls of the crew as they cast off from the dock of Sorrentina to set sail for France. Their voices made little impression; instead she heard the voice of the islands Tarot reader as she turned over each card for the babys reading.

The Queen of Swords.

Eight of Cups Reversed.

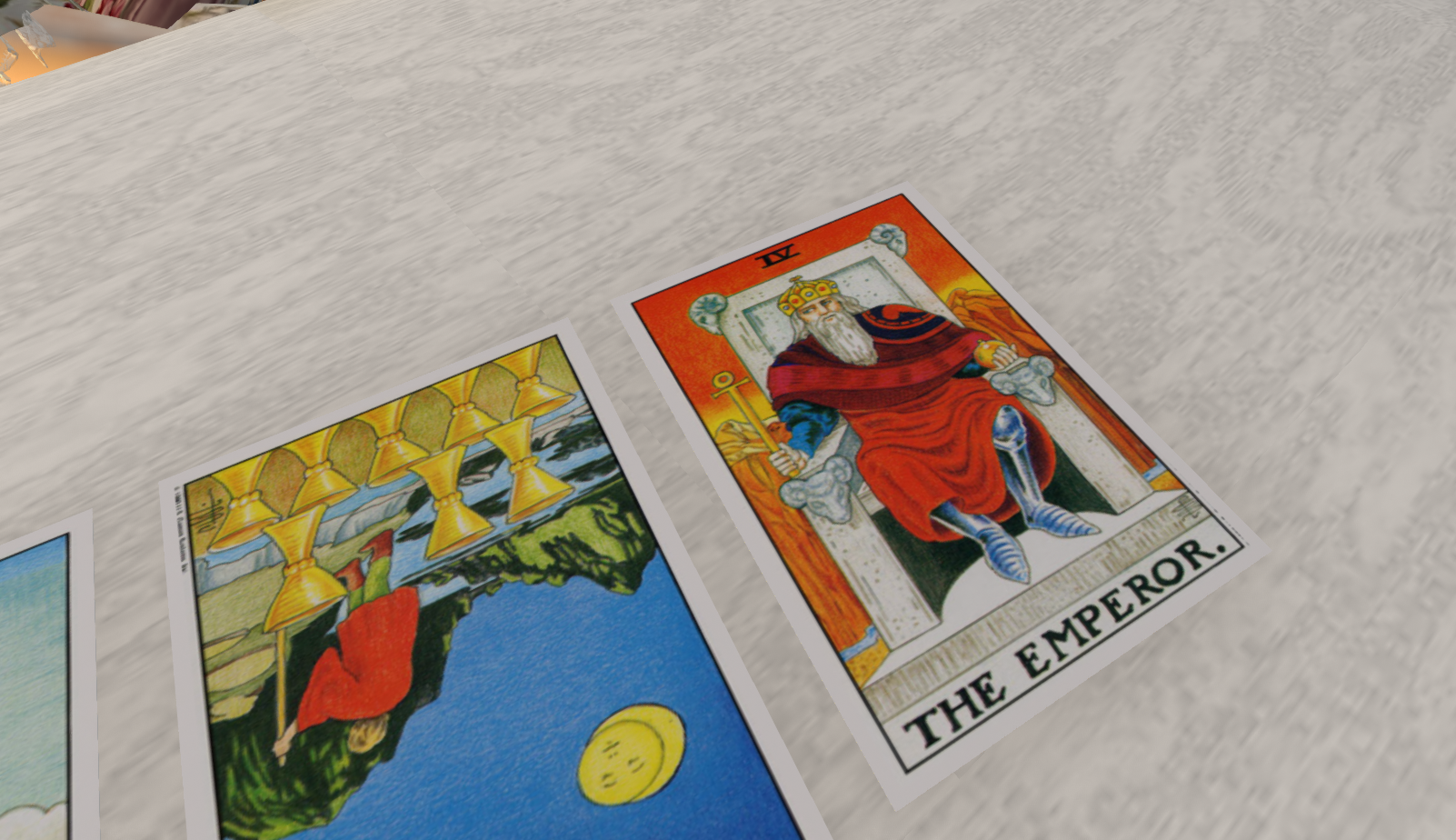

The Emperor.

A powerful trio and Lorsagne shivered as she recalled the card readers growing sense of purpose and wonder as she laid each card on the table.

Each card had carried a message. The Queen of Swords representing the childs birth mother watching over her daughter from heaven. The Cups indicating that the child would face challenges as well as possibilities for deep satisfaction.

Good portents. Yet it was the image of the final card symbolizing the father in the babys life that Lorsagne held in her minds eye. No, M. Gandt would not fill the role of a father in the childs life. That role would be filled by a man of power tempered by wisdom and experience, authority moderated by compassion, learning in the service of all people. This was to be the father figure in the childs life who would provide Lorsagne's godchild with lifelong guidance and advice.

Lorsagne had no doubt that the good Dottore Greymoon and his wife would prove loving and good parents, but the Tarot reading revealed that the baby was destined to live on a larger stage than Sorrentina. As her own godfather Fr. Camara had written her only the last month, Lorsagnes world was drawing to a close; the child could come to her maturity in a new century, a new world.

Lorsagne fell asleep with this thought, the muscles of her face relaxed, quiet. For once, the woman with no name except that of a minor aristocrat prisoner in the Bastille was wholly at peace.

Early-morning 11 August, 1784

Sorrentina docks

Lorsagne had no love of the sea, but the need to accomplish her business in both Paris and her home in the Haut-Medoc before returning to Sorrentina for her godchilds christening over-ruled her dislike of cramped, smelly cabins allotted to passengers whose money could buy speed of travel but precious little comfort.

Her belongings already stowed, she stretched herself out on the narrow cot in the tiny cabin and listened to the shouts and calls of the crew as they cast off from the dock of Sorrentina to set sail for France. Their voices made little impression; instead she heard the voice of the islands Tarot reader as she turned over each card for the babys reading.

The Queen of Swords.

Eight of Cups Reversed.

The Emperor.

A powerful trio and Lorsagne shivered as she recalled the card readers growing sense of purpose and wonder as she laid each card on the table.

Each card had carried a message. The Queen of Swords representing the childs birth mother watching over her daughter from heaven. The Cups indicating that the child would face challenges as well as possibilities for deep satisfaction.

Good portents. Yet it was the image of the final card symbolizing the father in the babys life that Lorsagne held in her minds eye. No, M. Gandt would not fill the role of a father in the childs life. That role would be filled by a man of power tempered by wisdom and experience, authority moderated by compassion, learning in the service of all people. This was to be the father figure in the childs life who would provide Lorsagne's godchild with lifelong guidance and advice.

Lorsagne had no doubt that the good Dottore Greymoon and his wife would prove loving and good parents, but the Tarot reading revealed that the baby was destined to live on a larger stage than Sorrentina. As her own godfather Fr. Camara had written her only the last month, Lorsagnes world was drawing to a close; the child could come to her maturity in a new century, a new world.

Lorsagne fell asleep with this thought, the muscles of her face relaxed, quiet. For once, the woman with no name except that of a minor aristocrat prisoner in the Bastille was wholly at peace.

Her vigil for the expectant mother and her child at an end, Lorsagne barely touches the light supper that she has ordered brought to her rooms. Without a purpose to drive her, she paces the small space, her brow furrowed, her lips set in a thin line that signals her discomfort. Catching sight of her reflection in the mirror of the small dressing table provided for her toilette, she stops and appraises the figure before her. Her eyes are dull, her cheeks sallow. Her reflection shows the first signs of aging: she is too fatigued to position her head so the jawline appears as firm as that of a girl.

The realization is enough to mobilize her will and she quickly readies herself for sleep that will allow her body time to erase traces of the worries of the week-long quarantine. Yet sleep does not come, so she leaves her bed and busies herself with more correspondence. For Lorsagne, relief comes from doing; in this she is more like a battle-hard soldier than a member of her sex.

The 9th day of August, 1784

Rocca Sorrentina

My cher Marie-Etienne Nitot,

News of your newest Court commissions reached me before I left Bordeaux. While your growing fame is a source of great satisfaction, I confess that my joy for my childhood friend is tempered by my anxiety that you may no longer possess the inclination for those small commissions for jewelry that I am so fond of placing with you.

My wrists and neck will never display your creations at Court, but I pray you will continue to help your old friend who counts on the fire and light of precious stones to conceal the fact that her flesh is no longer smooth and bears the marks of time. I fear I am growing old, dear friend and that is death for a vain woman.

But to the point. I have a commission I ask you to undertake immediately. A young woman has died this very day giving birth to a daughter. There is no husband and the young woman was estranged from her family. You may know of them, since her father is a goldsmith of some reputation in Roma. Her name was Maria Cecilia Antonacci. If you have knowledge of her family, you must share this information with me, for I am prepared to go to great effort to ensure that they accept the child of their own child.

So, you see your old friend is growing soft with the passage of years and distance from Paris. You must not speak of it, for it would do my reputation no service if it were known that I have mellowed and without reputation I stand no chance of seeing Papa ever released from the Bastille.

A small locket of the young mothers hair taken from her head moments after her passing by one of the Sisters who attended her during her final hours is enclosed.

I have no memento mori of my own mother and am hopeful that a small remembrance of her mother in the form of jewelry may provide the child comfort as she grows to adulthood. The fashion of the day calls for the weaving of the hair into the jewelrya mourning ring or brooch evidently being the current fashion. I have seen suitable pieces of such jewelry that possess both dignity and beauty, yet I would prefer something more ingenious and leave it to you to fashion something that will be both beautiful and of comfort to the child as she grows to maturity.

If you still have the pouch of Brazilian diamonds I left for you to use in a case to hold Luciens infernal cigars, perhaps you will feel they are appropriate to use instead in fashioning a piece for the child.

Whatever your decisions, do not delay, I will remain in Sorrentina long enough to see the baby settled with a decent family that has come forward should the babys own family choose not to accept her, but I must return to Bordeaux in time for the harvest.

A date has not been set for the babys christening, but I will stand as her god-mother and would hope to have the priest bless whatever you fashion with the mark of your atelier to memorialize her mother.

Until we meet again, I remain

Your childhood friend Lorsagne de Sade

Her vigil for the expectant mother and her child at an end, Lorsagne barely touches the light supper that she has ordered brought to her rooms. Without a purpose to drive her, she paces the small space, her brow furrowed, her lips set in a thin line that signals her discomfort. Catching sight of her reflection in the mirror of the small dressing table provided for her toilette, she stops and appraises the figure before her. Her eyes are dull, her cheeks sallow. Her reflection shows the first signs of aging: she is too fatigued to position her head so the jawline appears as firm as that of a girl.

The realization is enough to mobilize her will and she quickly readies herself for sleep that will allow her body time to erase traces of the worries of the week-long quarantine. Yet sleep does not come, so she leaves her bed and busies herself with more correspondence. For Lorsagne, relief comes from doing; in this she is more like a battle-hard soldier than a member of her sex.

The 9th day of August, 1784

Rocca Sorrentina

My cher Marie-Etienne Nitot,

News of your newest Court commissions reached me before I left Bordeaux. While your growing fame is a source of great satisfaction, I confess that my joy for my childhood friend is tempered by my anxiety that you may no longer possess the inclination for those small commissions for jewelry that I am so fond of placing with you.

My wrists and neck will never display your creations at Court, but I pray you will continue to help your old friend who counts on the fire and light of precious stones to conceal the fact that her flesh is no longer smooth and bears the marks of time. I fear I am growing old, dear friend and that is death for a vain woman.

But to the point. I have a commission I ask you to undertake immediately. A young woman has died this very day giving birth to a daughter. There is no husband and the young woman was estranged from her family. You may know of them, since her father is a goldsmith of some reputation in Roma. Her name was Maria Cecilia Antonacci. If you have knowledge of her family, you must share this information with me, for I am prepared to go to great effort to ensure that they accept the child of their own child.

So, you see your old friend is growing soft with the passage of years and distance from Paris. You must not speak of it, for it would do my reputation no service if it were known that I have mellowed and without reputation I stand no chance of seeing Papa ever released from the Bastille.

A small locket of the young mothers hair taken from her head moments after her passing by one of the Sisters who attended her during her final hours is enclosed.

I have no memento mori of my own mother and am hopeful that a small remembrance of her mother in the form of jewelry may provide the child comfort as she grows to adulthood. The fashion of the day calls for the weaving of the hair into the jewelrya mourning ring or brooch evidently being the current fashion. I have seen suitable pieces of such jewelry that possess both dignity and beauty, yet I would prefer something more ingenious and leave it to you to fashion something that will be both beautiful and of comfort to the child as she grows to maturity.

If you still have the pouch of Brazilian diamonds I left for you to use in a case to hold Luciens infernal cigars, perhaps you will feel they are appropriate to use instead in fashioning a piece for the child.

Whatever your decisions, do not delay, I will remain in Sorrentina long enough to see the baby settled with a decent family that has come forward should the babys own family choose not to accept her, but I must return to Bordeaux in time for the harvest.

A date has not been set for the babys christening, but I will stand as her god-mother and would hope to have the priest bless whatever you fashion with the mark of your atelier to memorialize her mother.

Until we meet again, I remain

Your childhood friend Lorsagne de Sade

Lorsagne shares news of the quarantine with her absent companion and recounts a theory of the origin of the Fever from the late-1600s ignored by the physicians of Europe

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-07

The evening of August 7, 1784

My dearest Capitane,

It is only my worry that you will learn of Sorrentinas difficulties from some careless gossip or the pages of the Gazette de Leyde and the Courrier dAvignon that leads me to disturb your peace with news my own.

I remain in Sorrentina, subject as are my traveling companions to the quarantine necessitated by the arrival of a ship carrying the Yellow Fever among its crew.

Do not be concerned, for I am well, having taken precautions.

As the Magistrates of Sorrentina told us of the outbreak of Fever, my mind presented me with images of you soon after your return from the American War of Independence. It was early-spring and we sat in vineyards, surrounded by newly pruned vines covered with unfurling leaves under the hard light of the Haut-Medoc, the sun warming your face cradled in my lap, your legs outstretched and your eyes drowsy with the effects of new wine. As you passed into sleep you described meetings between the Marquis de Lafayette and the American military leaders where you presented your calculation of the British losses during the 1780 summer campaigns against Revolutionary forces in Georgia, Florida and Carolina and concluded that Sir Henry Clintons siege of Charleston during the sickly months would ultimately prove the Britishs undoing.

Soon after your return from Yorktown, the Marquis conveyed an accounting of his debt to you for your analysis, confirming that Lord Cornwallis confessed that saving his army from another Carolina fever season led him to move north to Virginia as you predicted he wouldand there meet defeat in Yorktown where the American troops waited to engage him.

But enough of my proof to you of my attention to your battle tales! I also remembered the counsel Fr. Camara imparted to you as you prepared to depart for the Americas. Do you remember the pages he copied from a faded manuscript in the Societys possession and gave to you to carry to America? The author was known to Jesuits in Mexico and New Spain many years prior to the Suppression, a Jos de Patricio de los Ros who believed the Fever originated in tiny insects coming from lagoons.

Thanks be to God for godfathers scholarship, for like you, I heeded the wisdom of de los Rios and covered my skin and used my hand fan to keep air circulating about my person whenever I was about in Sorrentina. My wrists grew tired, but the mosquitos near the fountain in the plaza found no landing spot on my person.

Of the 500 souls of Sorrentina there have been few taken with the Fever, and I have no doubt that is due to the efficiency of the Magistrates and the cooperation of the citizens. Two doctors and nursing sisters from the mainland have cared for the sick and the well, exposing themselves to the disease with the confidence of those who know they do Gods work and trust in his protection. They have been spared.

One young womana traveler from Romawas less fortunate. As I write you late in the evening from the cool of my borrowed apartment, she remains in the Lazaretto, fighting for her own life and that of her child that is coming.

She has no husband. She is estranged from her family. I am moved by her plight and the similarity to that of my own mother. I pray you will understand that it is this young woman who keeps me in Sorrentina. I will not leave until her child is born and settled with a family who will give it a name and the security of a home other than that of an orphanage. I have written to the young woman offering to provide the necessary funds to sponsor the child, provide for its financial support and stand as its godmother.

Pray that the child and mother live and that my offer is accepted, and know that I do not sleep without thoughts of our reunion to comfort me.

Your Lorsagne

Lorsagne nails a letter to the door of the Lazaretto. It is addressed to the young woman who arrived from Roma

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-06

7 August, 1784

My dear SignorinaAntonacci,

Although a creature of few tender emotions, I can scarce contain my anguish as I consider the peril of your situation and that of the child you carry.

I sit in the comfort of rooms made available by kind souls of Sorrentina to travelers whose journeys have been interrupted by the quarantine and think of you in your sickbed far from your home and the comfort of those who would not wish to see you face this peril alone. Yes, you are currently estranged from your family but the gravity of your illness bids that I send word to your parents in hopes you and they will be reconciled while you still have life. I have sent word to them via the revenue ship that sailed this very day and pray you will forgive my intrusion.

I pray you will also forgive my impertinence in coming forward with an offer to sponsor your child in whatever manner proves most advantageous to that child. I am an orphan, and you could be the spirit of my own mother returned to earth so I could witness the depth of a mothers love as she willingly exchanges her life for her childs in the ordeal of birth. I pray that is not your fate, but you are gravely ill and if God takes you, I offer myself as god-mother and sponsor of the child. I cannot offer your child a home, but I can provide sufficient funds and property to secure a safe and loving home for your child so he or she will never face the shame and isolation of the orphanage.

There are others in Sorrentina also willing to offer assistance. You find yourself in a strange land, yet you are no stranger in our midst. Take strength from knowing that you and your child are a blessing for many.

May God spare your life and that of your child and take comfort that whatever God wills for your life, your child will not face life alone.

Lorsagne de Sade

Quarantine in Sorrentina - a letter to her godfather Fr. Jose Eusebio-Camara, SJ concerning an unborn child

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-06

6 August, Anno 1784

My dearest godfather and confessor,

I continue to be detained in Sorrentina as the yellow fever has come to the island, and all here are under quarantine. The authorities have taken measures to contain the sickness and physicians have tended both the sick and the well with courtesy and efficiency. I was given permission to leave after being examined, but have chosen to stay, missing our planned reunion in Venice within in the coming week.

Our visits are precious to me, yet I feel in my heart you will understand why I have chosen to remain in Sorrentina.

A young woman visiting the island has contracted the fever. I fear she will die very soon which is, of course, a sadness. That this young woman is great with child makes her death doubly painful, especially to an orphan who imagines the cries of the unborn child who will never know its mothers touch and devotion.

The young woman has no husband and no male has stepped forward and claim the child as his own. The woman confronted a gentleman here, a M. Gandt whom she believes to be her childs father, but he denies all knowledge of the woman. After writing M. Gandt in an attempt to persuade him to assume his responsibilities I am inclined to believe the young woman is mistaken. He does not appear to be deceiving when he says he cannot be the father.

So, dearest godfather, after prayers to St. Anne and to your beloved Ignatius of Loyola, I have discerned that God is directing me to give to this child the gift you gave to me at the time of my birth. When my dying mother laid me as an infant in your arms and asked you to oversee my immortal soul as godfather, you did not turn away. I will not turn away from this infant child should it live to be born. I will not leave Sorrentina until I see the baby has a name and a future beyond that of bastard orphan in a convent. I do not wish my own past on this child.

I pray you are safe and that you will forgive my absence. I remain your affectionate and grateful

Lorsagne

Lorsagne shares news of the quarantine with her absent companion and recounts a theory of the origin of the Fever from the late-1600s ignored by the physicians of Europe

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-07

The evening of August 7, 1784

My dearest Capitane,

It is only my worry that you will learn of Sorrentinas difficulties from some careless gossip or the pages of the Gazette de Leyde and the Courrier dAvignon that leads me to disturb your peace with news my own.

I remain in Sorrentina, subject as are my traveling companions to the quarantine necessitated by the arrival of a ship carrying the Yellow Fever among its crew.

Do not be concerned, for I am well, having taken precautions.

As the Magistrates of Sorrentina told us of the outbreak of Fever, my mind presented me with images of you soon after your return from the American War of Independence. It was early-spring and we sat in vineyards, surrounded by newly pruned vines covered with unfurling leaves under the hard light of the Haut-Medoc, the sun warming your face cradled in my lap, your legs outstretched and your eyes drowsy with the effects of new wine. As you passed into sleep you described meetings between the Marquis de Lafayette and the American military leaders where you presented your calculation of the British losses during the 1780 summer campaigns against Revolutionary forces in Georgia, Florida and Carolina and concluded that Sir Henry Clintons siege of Charleston during the sickly months would ultimately prove the Britishs undoing.

Soon after your return from Yorktown, the Marquis conveyed an accounting of his debt to you for your analysis, confirming that Lord Cornwallis confessed that saving his army from another Carolina fever season led him to move north to Virginia as you predicted he wouldand there meet defeat in Yorktown where the American troops waited to engage him.

But enough of my proof to you of my attention to your battle tales! I also remembered the counsel Fr. Camara imparted to you as you prepared to depart for the Americas. Do you remember the pages he copied from a faded manuscript in the Societys possession and gave to you to carry to America? The author was known to Jesuits in Mexico and New Spain many years prior to the Suppression, a Jos de Patricio de los Ros who believed the Fever originated in tiny insects coming from lagoons.

Thanks be to God for godfathers scholarship, for like you, I heeded the wisdom of de los Rios and covered my skin and used my hand fan to keep air circulating about my person whenever I was about in Sorrentina. My wrists grew tired, but the mosquitos near the fountain in the plaza found no landing spot on my person.

Of the 500 souls of Sorrentina there have been few taken with the Fever, and I have no doubt that is due to the efficiency of the Magistrates and the cooperation of the citizens. Two doctors and nursing sisters from the mainland have cared for the sick and the well, exposing themselves to the disease with the confidence of those who know they do Gods work and trust in his protection. They have been spared.

One young womana traveler from Romawas less fortunate. As I write you late in the evening from the cool of my borrowed apartment, she remains in the Lazaretto, fighting for her own life and that of her child that is coming.

She has no husband. She is estranged from her family. I am moved by her plight and the similarity to that of my own mother. I pray you will understand that it is this young woman who keeps me in Sorrentina. I will not leave until her child is born and settled with a family who will give it a name and the security of a home other than that of an orphanage. I have written to the young woman offering to provide the necessary funds to sponsor the child, provide for its financial support and stand as its godmother.

Pray that the child and mother live and that my offer is accepted, and know that I do not sleep without thoughts of our reunion to comfort me.

Your Lorsagne