Early morning, 18 August 1784

Maison Diamante, Marseille

Lorsagne did not share the common belief that soaking in waterespecially hot waterwould permit disease to enter her body, and she was pleased to see that the finely finished and furnished room provided for her use in de Saboulin Bollenas house known as Maison Diamante contained a large copper bathtub, as well as an enormous tile stove capable of heating both the room and the requisite water she would need to wash away the grime of the journey from Sorrentina to Marseille.

The servant assigned to tend to her needs disapproved, of course, but the woman had followed Lorsagnes instruction to have the tub filled with hot water at dawn so Lorsagne could begin her day with a bath infused with lavender, mint, and dried iris flowers. Fresh linen garments were simply no substitute for a long soak to Lorsagnes mind and she used the time in her bath to review what she had learned the previous evening over a long and felicitous dinner with her godfather and their host, a representative of the powerful and ancient house of Saboulin Bollena, one of Marseilles premier ship-owners trading with ports of the Levant as well as the West Indies.

Splashing the now cooling water over her breasts she laughed recalling how Saboulin Bollena had come to her defense when she protested to her godfather that she needed a day of rest on land before once again boarding a ship where she would be subject to the discomfort that always accompanied her when she was forced to travel by sea. Saboulin Bollena had interjected that he, too, suffered from chronic seasickness that no amount of ginger could alleviate and convinced her godfather that a days delay would allow him to ensure the ship he was putting at their disposal was well-provisioned and that its captain and crew were both skilled and discrete.

Considering that the presence of Lorsagnes godfather in France defied the orders of both the French king and the pope, discretion was a compelling argument against which Camara had made no objection.

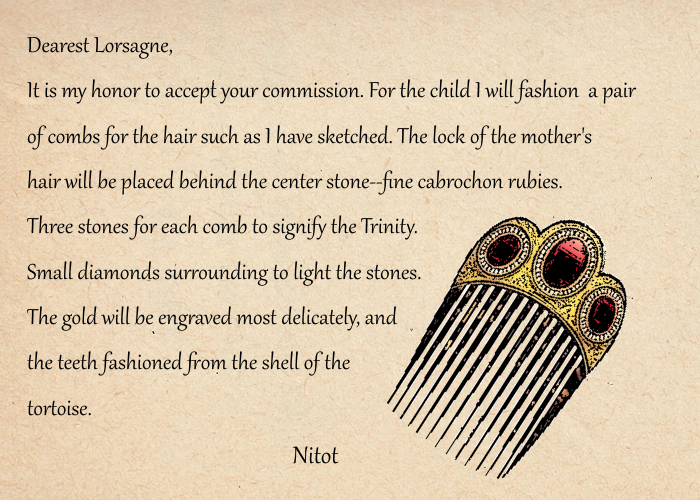

Rising from her bath and attended by the serving woman who wrapped her in warmed linen sheets, Lorsagne turned her thoughts to the small packet of correspondence her godfather had given her the evening before. She would spend the day writing and dispatching her replies, beginning with the Parisian jeweler to whom she had given the commission to create a suitable christening gift for her godchild Maria and ending with a response to Capitane Lucien de Robion-Castellanes worrisome report about her friend Fannys young solider, Lt. Henri Badeau.

Early morning, 18 August 1784

Maison Diamante, Marseille

Lorsagne did not share the common belief that soaking in waterespecially hot waterwould permit disease to enter her body, and she was pleased to see that the finely finished and furnished room provided for her use in de Saboulin Bollenas house known as Maison Diamante contained a large copper bathtub, as well as an enormous tile stove capable of heating both the room and the requisite water she would need to wash away the grime of the journey from Sorrentina to Marseille.

The servant assigned to tend to her needs disapproved, of course, but the woman had followed Lorsagnes instruction to have the tub filled with hot water at dawn so Lorsagne could begin her day with a bath infused with lavender, mint, and dried iris flowers. Fresh linen garments were simply no substitute for a long soak to Lorsagnes mind and she used the time in her bath to review what she had learned the previous evening over a long and felicitous dinner with her godfather and their host, a representative of the powerful and ancient house of Saboulin Bollena, one of Marseilles premier ship-owners trading with ports of the Levant as well as the West Indies.

Splashing the now cooling water over her breasts she laughed recalling how Saboulin Bollena had come to her defense when she protested to her godfather that she needed a day of rest on land before once again boarding a ship where she would be subject to the discomfort that always accompanied her when she was forced to travel by sea. Saboulin Bollena had interjected that he, too, suffered from chronic seasickness that no amount of ginger could alleviate and convinced her godfather that a days delay would allow him to ensure the ship he was putting at their disposal was well-provisioned and that its captain and crew were both skilled and discrete.

Considering that the presence of Lorsagnes godfather in France defied the orders of both the French king and the pope, discretion was a compelling argument against which Camara had made no objection.

Rising from her bath and attended by the serving woman who wrapped her in warmed linen sheets, Lorsagne turned her thoughts to the small packet of correspondence her godfather had given her the evening before. She would spend the day writing and dispatching her replies, beginning with the Parisian jeweler to whom she had given the commission to create a suitable christening gift for her godchild Maria and ending with a response to Capitane Lucien de Robion-Castellanes worrisome report about her friend Fannys young solider, Lt. Henri Badeau.

Late-afternoon, 17thof August, 1784

Godfather!

Even in the dim light of the small sacristy, there was no mistaking the sole occupant who waited for Lorsagne, and it gave the old man joy to see his godchilds normally guarded face break into the smile of a child: open, trusting and full of joy.

His passenger delivered safely to his old teacher and confessor, de Saboulin Bollena turned to leave, knowing that another carriage awaited behind the basilica that would take the exiled Jesuit and his godchild to his own house for safekeeping, rest and refreshment before beginning the next leg of their journey. He would join the two this evening for dinner and conversation, and de Saboulin Bollena smiled to himself at the prospect of the Jesuits discomfort when he would have to tell the woman that she would not be traveling to Paris or Bordeaux but would instead be returning to Sorrentina in less than a days time.

Late-afternoon, 17thof August, 1784

Godfather!

Even in the dim light of the small sacristy, there was no mistaking the sole occupant who waited for Lorsagne, and it gave the old man joy to see his godchilds normally guarded face break into the smile of a child: open, trusting and full of joy.

His passenger delivered safely to his old teacher and confessor, de Saboulin Bollena turned to leave, knowing that another carriage awaited behind the basilica that would take the exiled Jesuit and his godchild to his own house for safekeeping, rest and refreshment before beginning the next leg of their journey. He would join the two this evening for dinner and conversation, and de Saboulin Bollena smiled to himself at the prospect of the Jesuits discomfort when he would have to tell the woman that she would not be traveling to Paris or Bordeaux but would instead be returning to Sorrentina in less than a days time.

17th of August, 1784

Marseille, France

Lorsagne loved the human commotion of ports, and the Port of Marseille, Frances premiere military and merchant port with access to Frances inland waterways via the River Rhone was no exception.

Once she and her belongings reached shore and her feet were once again planted on solid land she handed off a letter to a young man eager for work instructing him to wait for a reply and showing him a small handful of coins that would be his once he returned. Counting the coins in her palm, the young man took off at a run; Lorsagne bargained he would return within the hour.

An hour standing on the docks in the heat of a late-summer Provence afternoon was bearable, so parasol in hand and surrounded by her small pile of chests accompanying her from Sorrentina, she watched as a great Spanish ship arriving from Cadiz disgorged the wealth of Spanish America: indigo from Guatemala, leather from Buenos Aires, copper from Peru and Mexico, wool, cocoa from Caracas, vanilla, gold, silver. A dozen barrels rolled off the ship as she watched, whisked away by scruffy porters who took their direction from burly lookouts. Smugglers, Lorsagne thought, and likely the wine was Spanish brought into France as contraband. As a vigneron in a place where the purity of wine was a reflection of both respect and pride in the soil that nourished the vines and brought forth new life with all its promise each year, Lorsagne could not help but hold the tainted Spanish wine in contempt. At the same time she understood the ease and the appeal of the deception; she told herself that if the making of wine held no profit, it would hold no interest for her.

Lorsagne was calculating the expenseand the potentialof the coming harvest when she saw the handsome calche approach. The youth she had sent to deliver her message was running along side the handsome two-seated open carriage with a falling hood. A pair of heavy muscled Arabians that pulled the vehicle came to a stop, standing nearly motionless with a seeming disdain for their surroundings. Magnificent creatures and they and the carriage drew stares of laborers, merchants and travelers alike. The armorial bearings on the carriage door confirmed the owners identity, and as she crossed the few steps to the waiting vehicle Lorsagne drew down her parasol, said a silent prayer of thanks for the breadth of her godfathers contacts, and handed the promised coins to the youth who had delivered her message.

The coachman arranged a small portable step to permit Lorsagne ease of access. Giving him her gloved hand she entered the low-riding vehicle easily, settling herself beside the carriages only other occupant. Her chests secured to the undercarriage, she and her companion left the dock, making their way through the ports crowded streets headed to the low hills surrounding the Bay of Marseille in the direction of a fortress and basilica built in the 13th and 16th centuries at the highest point of Marseille, a limestone peak known as "La Garde" rising to a height of more than 160 meters. The combined fort and basilica were visible from every point in Marseille. Standing proud, glowing in the reflected heat of terraced stone pathways and bathed in the hard brilliant sunlight of Provence the inhabitants of Marseille referred to the basilica as Notre Dame de la Garde: the good mother who watched over Frances gateway to the Mediterranean.

Like the Tarot reading for the newborn, Lorsagne took her destination as an omen. As she and her companion walked the length of the basilica to reach a small door towards the back, Lorsagne drew the hood of her traveling cloak over her head and entered the stone building unobserved.

17th of August, 1784

Marseille, France

Lorsagne loved the human commotion of ports, and the Port of Marseille, Frances premiere military and merchant port with access to Frances inland waterways via the River Rhone was no exception.

Once she and her belongings reached shore and her feet were once again planted on solid land she handed off a letter to a young man eager for work instructing him to wait for a reply and showing him a small handful of coins that would be his once he returned. Counting the coins in her palm, the young man took off at a run; Lorsagne bargained he would return within the hour.

An hour standing on the docks in the heat of a late-summer Provence afternoon was bearable, so parasol in hand and surrounded by her small pile of chests accompanying her from Sorrentina, she watched as a great Spanish ship arriving from Cadiz disgorged the wealth of Spanish America: indigo from Guatemala, leather from Buenos Aires, copper from Peru and Mexico, wool, cocoa from Caracas, vanilla, gold, silver. A dozen barrels rolled off the ship as she watched, whisked away by scruffy porters who took their direction from burly lookouts. Smugglers, Lorsagne thought, and likely the wine was Spanish brought into France as contraband. As a vigneron in a place where the purity of wine was a reflection of both respect and pride in the soil that nourished the vines and brought forth new life with all its promise each year, Lorsagne could not help but hold the tainted Spanish wine in contempt. At the same time she understood the ease and the appeal of the deception; she told herself that if the making of wine held no profit, it would hold no interest for her.

Lorsagne was calculating the expenseand the potentialof the coming harvest when she saw the handsome calche approach. The youth she had sent to deliver her message was running along side the handsome two-seated open carriage with a falling hood. A pair of heavy muscled Arabians that pulled the vehicle came to a stop, standing nearly motionless with a seeming disdain for their surroundings. Magnificent creatures and they and the carriage drew stares of laborers, merchants and travelers alike. The armorial bearings on the carriage door confirmed the owners identity, and as she crossed the few steps to the waiting vehicle Lorsagne drew down her parasol, said a silent prayer of thanks for the breadth of her godfathers contacts, and handed the promised coins to the youth who had delivered her message.

The coachman arranged a small portable step to permit Lorsagne ease of access. Giving him her gloved hand she entered the low-riding vehicle easily, settling herself beside the carriages only other occupant. Her chests secured to the undercarriage, she and her companion left the dock, making their way through the ports crowded streets headed to the low hills surrounding the Bay of Marseille in the direction of a fortress and basilica built in the 13th and 16th centuries at the highest point of Marseille, a limestone peak known as "La Garde" rising to a height of more than 160 meters. The combined fort and basilica were visible from every point in Marseille. Standing proud, glowing in the reflected heat of terraced stone pathways and bathed in the hard brilliant sunlight of Provence the inhabitants of Marseille referred to the basilica as Notre Dame de la Garde: the good mother who watched over Frances gateway to the Mediterranean.

Like the Tarot reading for the newborn, Lorsagne took her destination as an omen. As she and her companion walked the length of the basilica to reach a small door towards the back, Lorsagne drew the hood of her traveling cloak over her head and entered the stone building unobserved.

The voyage from Sorrentina to Marseille - Fresh figs, Signora McBain's coffee, and time for correspondence

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-15

August, 1784

From the time Lorsagne made the decision to book passage for Marseilles, her maid Perrette had less than twelve hours to pack everything her mistress would need for the journey. The two-masted Minerva would cast off from Sorrentina at dawn, and the young woman who had served Lorsagne for the past several years worked through the night to pack de Sades belongings and to secure the additional supplies her mistress would need to make the sea-voyage with as little discomfort as possible.

Lorsagnes books, several letter cases, and her brass-handled writing box fitted with seals and sealing-wax, notepaper, nibs and a pen-shaft were packed first. Next, travel clothing and articles of toilette were chosen. The bulk of Lorsagnes wardrobe would be kept on the island in anticipation of Lorsagnes return. While Perrette sorted through wigs, gowns, cloaks, slippers, hats, corsets and chemises, Lorsagne tended to her jewelry and other items of a personal nature she did not wish the maid to handle. Sending Perrette to the baker to await the first loaves of fresh bread, Lorsagne packed her jewelry in soft flannel pouches secured with fine silk cording which she then secured around her waist so the bags would be hidden by her skirt.

By the time Lorsagne finished dressing, Perette returned with food to sustain Lorsagne during the four-day voyage from Sorrentina to the busy port of Marseilles. Freshly baked flatbread was laid atop lidded baskets packed with sweet butter, local cheese, cured mutton, almonds, fat lemons, figs, and local stone fruits whose ripe scent would help mask the fetid odors of the ships small cabin. Lorsagne laughed at the mounds of food, telling Perette she would grow fat and that it would be the girls fault.

All was ready, and Perette summoned two young male servants to load a waiting cart with her mistresss belonging and take them to the docks where strong-backed sailors would convey them to the waiting ship and use stout rope to firmly secure all of Lorsagnes belongings in the tiny cabin Lorsagne had been able to book.

Lorsagne and Perette accompanied the porters, with Lorsagne carrying a small package Signora McBain had delivered to her rooms moments before she took her leave. Lorsagne held the package to her chest tightly, inhaling the rich fragrance of the Signoras prized coffee beans freshly roasted and ground fine to permit her the luxury of fresh coffee to revive the bodyand to mask the taste of the ration of brackish water that Lorsagne would be allotted on her trip. Perette carried two small casks of brandy as additional assurance that Lorsagne would be able to use a share of her allotment of fresh water for hygiene instead of being forced to drink water stored in wooden casks and often fouled by slime.

In the several minutes it took the small party to reach the docks, Perette and the two porters chatted in the way of young people, their soft laughter breaking the silence of the early hour. Lorsagne was quiet, listening to her own thoughts and memories of Sorrentina and the cry of sea birds taking flight as the sky began to lighten.

Perette would stay in Sorrentina; Lorsagne would travel faster alone and she wanted the keen-eyed serving girl to keep an eye on her possessionsand her interestsin her absence. As they made their farewells, Lorsagne slipped a heavy envelope into Perettes hands instructing her not to break the seal and extract the contents unless Lorsagne failed to return within three months time. When the girl attempted to query Lorsagne about the letters contents, she was rebuked with uncharacteristic harshness. Downcast and puzzled, Perette slipped the envelope into her skirt pocket and watched as Lorsagne boarded the skiff that would carry her from the dock to the waiting vessel.

Within minutes, Lorsagnes form was swallowed by the early-morning fog and Perette made her way back to her mistresss rooms still stinging from her chastisement, wondering if the letter was a portent of dangers of which she had no knowledge, and resigned that while fair-minded and generous, her mistress would remain as much of a mystery as the implacable small plaster icons of the saints to whom she prayed when she sought favors and forgiveness.

+++

By the second day at sea, the effects of waters made rough by late-summer heat and strong crosswinds left Lorsagne with little appetite. She kept to her cabin and wrote letters by the hour. Possessed of a fine hand, a keen eye for observing her surroundings and sufficient wit to render her impressionsand her aimswith ease and clarity, Lorsagne enjoyed a wide-ranging and effective correspondence with persons useful to her interests. The developments in Sorrentina would call on all of Losagnes contacts, and Lorsagne used her time at sea to begin the process of securing a place in the world for her godchild. She wrote with few interruptions, and although Perette had managed to secure 30 sheets of parchment, the supply was exhausted by the third day.

By the fourth day, Lorsagnes supply of fresh food was also depleted, and as the ship anchored some several hundred feet from the docks of Marseilles, Lorsagne was impatient to disembark, make arrangements for delivery of her correspondence, and secure a coach and four for the long overland journey home. She had one detour to make before she would reach The Haven: the Bastille. It was not a stop she wished to make, but Lorsagne feared the repercussions should she fail to present herself as requested in the letter she had received days before leaving Sorrentina.

The voyage from Sorrentina to Marseille - Fresh figs, Signora McBain's coffee, and time for correspondence

By Lorsagne de Sade, 2014-08-15

August, 1784

From the time Lorsagne made the decision to book passage for Marseilles, her maid Perrette had less than twelve hours to pack everything her mistress would need for the journey. The two-masted Minerva would cast off from Sorrentina at dawn, and the young woman who had served Lorsagne for the past several years worked through the night to pack de Sades belongings and to secure the additional supplies her mistress would need to make the sea-voyage with as little discomfort as possible.

Lorsagnes books, several letter cases, and her brass-handled writing box fitted with seals and sealing-wax, notepaper, nibs and a pen-shaft were packed first. Next, travel clothing and articles of toilette were chosen. The bulk of Lorsagnes wardrobe would be kept on the island in anticipation of Lorsagnes return. While Perrette sorted through wigs, gowns, cloaks, slippers, hats, corsets and chemises, Lorsagne tended to her jewelry and other items of a personal nature she did not wish the maid to handle. Sending Perrette to the baker to await the first loaves of fresh bread, Lorsagne packed her jewelry in soft flannel pouches secured with fine silk cording which she then secured around her waist so the bags would be hidden by her skirt.

By the time Lorsagne finished dressing, Perette returned with food to sustain Lorsagne during the four-day voyage from Sorrentina to the busy port of Marseilles. Freshly baked flatbread was laid atop lidded baskets packed with sweet butter, local cheese, cured mutton, almonds, fat lemons, figs, and local stone fruits whose ripe scent would help mask the fetid odors of the ships small cabin. Lorsagne laughed at the mounds of food, telling Perette she would grow fat and that it would be the girls fault.

All was ready, and Perette summoned two young male servants to load a waiting cart with her mistresss belonging and take them to the docks where strong-backed sailors would convey them to the waiting ship and use stout rope to firmly secure all of Lorsagnes belongings in the tiny cabin Lorsagne had been able to book.

Lorsagne and Perette accompanied the porters, with Lorsagne carrying a small package Signora McBain had delivered to her rooms moments before she took her leave. Lorsagne held the package to her chest tightly, inhaling the rich fragrance of the Signoras prized coffee beans freshly roasted and ground fine to permit her the luxury of fresh coffee to revive the bodyand to mask the taste of the ration of brackish water that Lorsagne would be allotted on her trip. Perette carried two small casks of brandy as additional assurance that Lorsagne would be able to use a share of her allotment of fresh water for hygiene instead of being forced to drink water stored in wooden casks and often fouled by slime.

In the several minutes it took the small party to reach the docks, Perette and the two porters chatted in the way of young people, their soft laughter breaking the silence of the early hour. Lorsagne was quiet, listening to her own thoughts and memories of Sorrentina and the cry of sea birds taking flight as the sky began to lighten.

Perette would stay in Sorrentina; Lorsagne would travel faster alone and she wanted the keen-eyed serving girl to keep an eye on her possessionsand her interestsin her absence. As they made their farewells, Lorsagne slipped a heavy envelope into Perettes hands instructing her not to break the seal and extract the contents unless Lorsagne failed to return within three months time. When the girl attempted to query Lorsagne about the letters contents, she was rebuked with uncharacteristic harshness. Downcast and puzzled, Perette slipped the envelope into her skirt pocket and watched as Lorsagne boarded the skiff that would carry her from the dock to the waiting vessel.

Within minutes, Lorsagnes form was swallowed by the early-morning fog and Perette made her way back to her mistresss rooms still stinging from her chastisement, wondering if the letter was a portent of dangers of which she had no knowledge, and resigned that while fair-minded and generous, her mistress would remain as much of a mystery as the implacable small plaster icons of the saints to whom she prayed when she sought favors and forgiveness.

+++

By the second day at sea, the effects of waters made rough by late-summer heat and strong crosswinds left Lorsagne with little appetite. She kept to her cabin and wrote letters by the hour. Possessed of a fine hand, a keen eye for observing her surroundings and sufficient wit to render her impressionsand her aimswith ease and clarity, Lorsagne enjoyed a wide-ranging and effective correspondence with persons useful to her interests. The developments in Sorrentina would call on all of Losagnes contacts, and Lorsagne used her time at sea to begin the process of securing a place in the world for her godchild. She wrote with few interruptions, and although Perette had managed to secure 30 sheets of parchment, the supply was exhausted by the third day.

By the fourth day, Lorsagnes supply of fresh food was also depleted, and as the ship anchored some several hundred feet from the docks of Marseilles, Lorsagne was impatient to disembark, make arrangements for delivery of her correspondence, and secure a coach and four for the long overland journey home. She had one detour to make before she would reach The Haven: the Bastille. It was not a stop she wished to make, but Lorsagne feared the repercussions should she fail to present herself as requested in the letter she had received days before leaving Sorrentina.